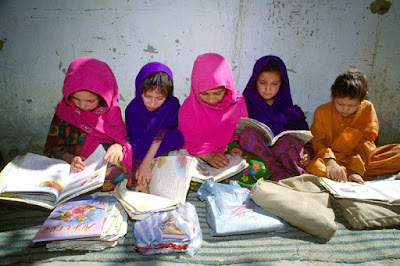

The picture of illiteracy in Pakistan is grim. Although successive governments have announced various programmes to promote literacy, especially among women, they have been unable to translate their words into action because of various political, social and cultural obstacles.

Official statistics released by the Federal Education Ministry of Pakistan give a desperate picture of education for all, espcially for girls. The overall literacy rate is 46 per cent, while only 26 per cent of girls are literate. Independent sources and educational experts, however, are sceptical. They place the overall literacy rate at 26 per cent and the rate for girls and women at 12 per cent, contending that the higher figures include people who can handle little more than a signature. There are 163,000 primary schools in Pakistan, of which merely 40,000 cater to girls. Of these, 15,000 are in Punjab Province, 13,000 in Sind, 8,000 in North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) and 4,000 in Baluchistan.

Similarly, out of a total 14,000 lower secondary schools and 10,000 higher secondary schools, 5,000 and 3,000 respectively are for girls, in the same decreasing proportions as above in the four provinces. There are around 250 girls colleges, and two medical colleges for women in the public sector of 125 districts. Some 7 million girls under 10 go to primary schools, 5.4 million between 10 and 14 attend lower secondary school, and 3 million go to higher secondary schools. About 1.5 million and 0.5 million girls respectively go to higher secondary schools/colleges and universities.

Alarming situation in rural areas

The situation is especially alarming in rural areas due to social and cultural obstacles. One of the most deplorable aspects is that in some places, particularly northern tribal areas, the education of girls is strictly prohibited on religious grounds. This is a gross misinterpretation of Islam, the dominant religion in Pakistan (96 per cent of the population), which like all religions urges men and women to acquire education.

The situation is the most critical in NWFP and Baluchistan, where the female literacy rate stands between 3 per cent and 8 per cent. Some government organizations and non-governmental organizations have tried to open formal and informal schools in these areas, but the local landlords, even when they have little or nothing to do with religion or religious parties, oppose such measures, apparently out of fear that people who become literate will cease to follow them with blind faith. Unfortunately, the government has not so far taken any steps to promote literacy or girls= education in these areas. It is even reluctant to help NGOs or other small political or religious parties do the job, because in order to maintain control, it needs the support of these landlords and chieftains who, as members of the two major political parties, are regularly elected to the national assembly.

"I want to go to school to learn but I cannot because my parents do not allow me to do so," said 9-year old Palwasha, who has visited the biggest city of Pakistan, Karachi, with her parents and seen girls like herself going to school. She lives in a village located in Dir district (NWFP), where education for girls does not exist. "We have only one school for boys," she said, adding, Aone of my friends goes school, but she is now in Peshawar (capital city of NWFP)".

Work but no school

Poverty is also a big hurdle in girls' education. According to UNICEF, 17.6 per cent of Pakistani children are working and supporting their families. Indeed, children working as domestic help is a common phenomenon in Pakistan, and this sector employs more girls than boys.

"Khanzadi, [a 10-year old girl with blue eyes working in a rich neighbourhood of Karachi] is lucky she's with us, her mistress says "We can spare some food and help her grow". But Khanzadi is miserable. Every day when she sees girls like herself going to school she becomes restless, but she has to stay in the house and do all the work.

Jamila, 11, also works as a domestic servant. At first her job was only to look after the baby , but as she grew older , the other servant in charge of housecleaning and cooking was dismissed and Jamila was asked to do all the work. "I want to go to school like other children, but my parents can't afford it. So I have to work and help support my family, she said. In big cities and towns, people are joining together to send their daughters to school. In any case, because of better facilities, girls' literacy is higher in big cities such as Karachi, Lahore, Islamabad, Rawalpindi, Faisalabad, Hyderabad, Gujranwala, Peshawar and Quetta.

Ray of hope

Even though there is a lack of concern on the part of government to promote girls' education, some religious groups, political parties and NGOs are working actively to do so despite all barriers.

Alkhidmat, a countrywide NGO, is running almost 100 non-formal schools in small villages of Sind, Baluchistan and NWFP Provinces, where not merely girls but adult women are admitted for basic primary education.

"We think women's education is equally important. When women become literate, they can build a better nation, said Mrs Abida Farheen, a graduate of Karachi university and the head of Alkhidmat's education wing.

In Sind province, NAZ, a Khairpur-based NGO, is running fifty formal and non-formal girls' schools in the city's outskirts; the NGO Resource Center, a Karachi-based organisation, is operating scores of girls' schools while Green Crescent, another Karachi-based NGO, is running twenty non-formal schools for girls in villages throughout the province. In Punjab, the Al-Ghazali Education Trust, a Lahore-based organization, is operating some 200 formal and non-formal schools, mostly for girls and women, all over the province.

Government efforts

The ousted government of Nawaz Sharif had introduced the idea of non-formal education for women throughout the country. To do this, he had established the prime minister's literacy commission and was preparing to set up some 100,000 non-formal schools for girls and women. But now the project is in the doldrums because of the change of government and continuing political instability is seriously jeopardizing its future. Nonetheless, some 1,500 non-formal schools for girls and women, set up under former prime minister Benazir Bhutto and President Zia ul-Haq, continue to function in rural areas.

Although the media have played an effective role in convincing people to send their daughters to schools, the situation remains dramatic in the villages and small towns where almost 70 per cent of the country's population resides.

0 Comments